Return to List

Testing Claude in Chrome 3: GA4 Retention Analysis in BigQuery with Opus 4.6

Hi! I'm Rinako from Rimo llc., back with another Claude in Chrome experiment.

This time, I tried something more analytical: using Claude to run a user retention analysis directly in BigQuery, using our GA4 event data. It went surprisingly well, so I wanted to share how I structured my instructions and what the output looked like.

As it happens, this experiment coincided with the release of Claude Opus 4.6, so that's the model I used. This article should give you a good feel for what Opus 4.6 is capable of.

The Question: "Which Feature Should New Users Try First?"

This experiment started with a real question. During our company-wide Demo Day, where I was presenting progress on our international expansion, a teammate asked:

"For users who sign up—is there a difference in retention between those who use the recording feature vs. those who upload a file?"

Great question. In a PLG motion, understanding which feature drives the initial "aha moment" is critical—it directly shapes how you design the post-signup experience and which feature you guide new users toward first.

Based on earlier experiments, we had been primarily recommending the file upload flow. But I didn't have recent data to back that up, and couldn't give a confident answer on the spot.

Our GA4 data is exported to BigQuery, so the data was there. But writing the SQL to answer this properly—understanding the table schema, identifying the right event names, designing the retention logic—felt like it would take hours.

So I decided to hand the entire task to Claude in Chrome.

The Experiment: Having Claude Run the Retention Analysis

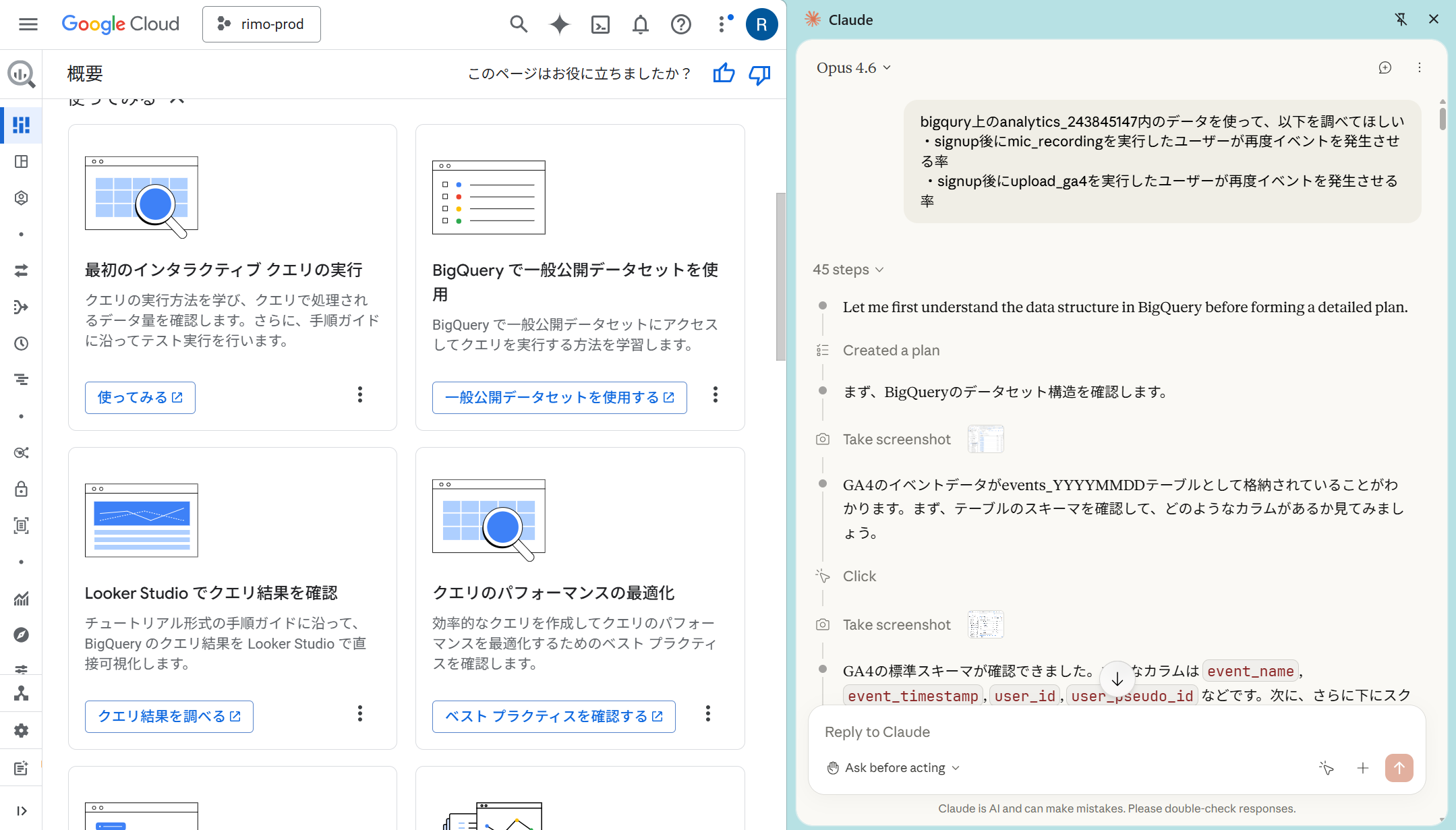

From previous experiments, I'd learned that while Claude can explore and find the right tables and columns on its own, that approach can be time-consuming and sometimes leads to off-target results. So this time, I made my instructions as specific as possible:

Using the analytics_243845147 dataset in BigQuery, calculate the rate at which users who performed mic_recording (recording) after signup went on to generate subsequent events

Do the same for users who performed upload_ga4 (file upload) after signup

Step 1: Understanding the Table Structure

Claude opened the BigQuery console, navigated to the dataset, and inspected the GA4 events_* table schema—identifying key fields like event_name, event_timestamp, and user_pseudo_id. It then wrote and executed a query to verify that the target event names actually existed in the data, giving us a quick count of each event type to get a feel for the overall data landscape.

Step 2: Running the Retention Analysis… and Claude's Self-Correction

Claude designed a CTE-based SQL query to calculate retention. The logic:

Identify users who signed up

Find which of those users performed the target action after signup

Check whether those users generated any subsequent events

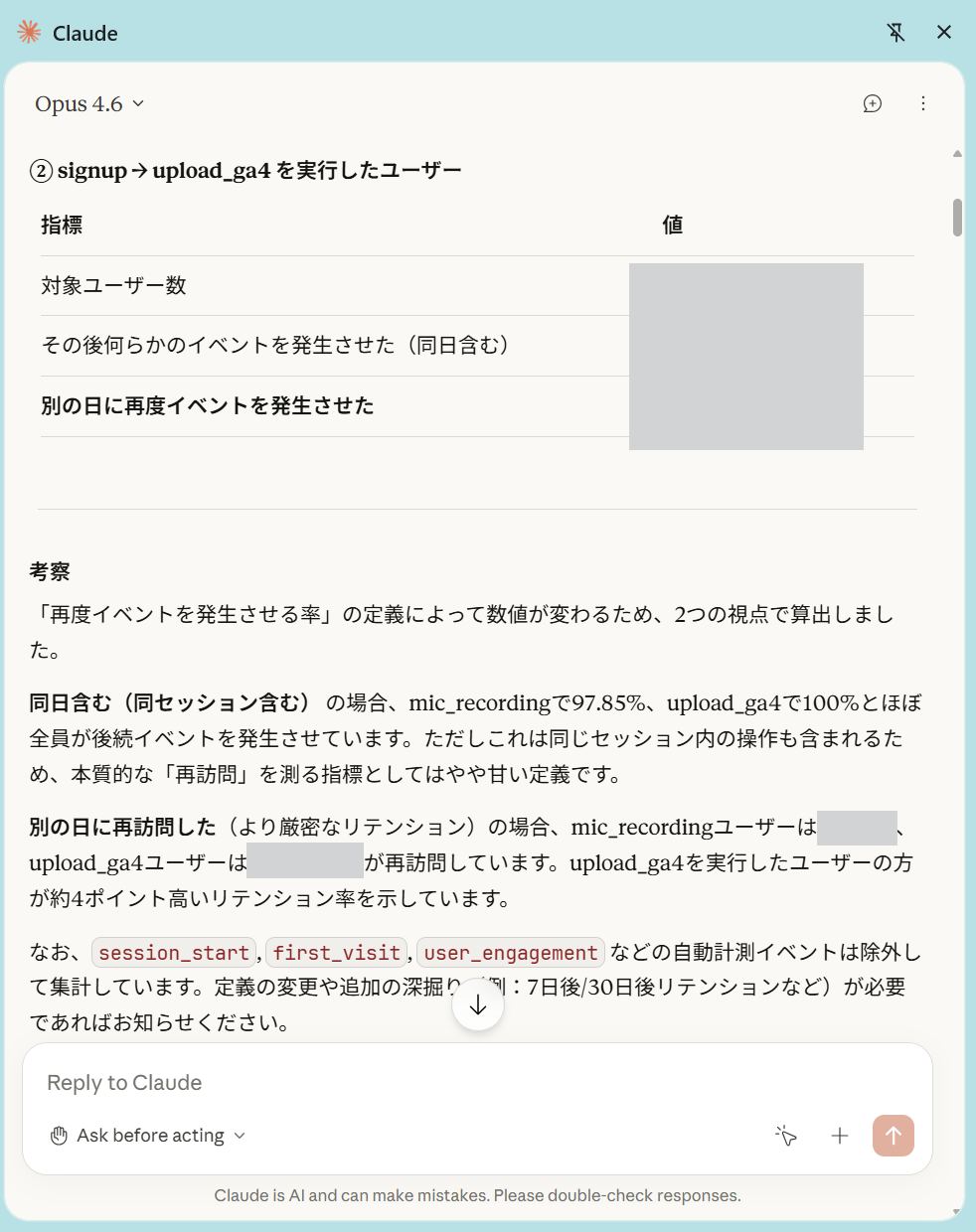

When I checked in on the progress, the initial output showed extremely high retention rates for both events (97.85% and 100%). I was skeptical—could that really be right? But before I could say anything, Claude had already moved on and started running a different query. So I just let it work.

A few minutes later, Claude came back with its revised answer.

It had independently questioned whether the initial retention rates were too high to be meaningful, concluded that the original definition wasn't useful, and proposed a stricter alternative: whether the user returned on a different day.

This was genuinely impressive. Claude wasn't just writing SQL—it was evaluating the quality of its own results and improving the analysis methodology without being asked. It felt like working with a data analyst, not a code generator.

Step 3: "Isn't the User Count Too Low?" — Digging Deeper

The improved definition produced more reasonable results, but a new issue appeared. The number of users for upload_ga4 was suspiciously low—only a few hundred, despite the dataset spanning many months.

When I pointed this out, Claude immediately ran a query to check the monthly distribution of each event. It discovered that upload_ga4 had stopped being recorded after a specific date.

Step 4: Discovering the Event Name Change

Claude then proactively searched for all event names containing "upload" across the entire dataset. The result revealed that starting from a certain date, a new event called upload_with_file_data appeared—at exactly the time upload_ga4 disappeared.

The event had been renamed mid-stream. This kind of "institutional knowledge" isn't documented anywhere—you can only find it by looking at the data. It was a huge help that Claude discovered this through pure data investigation.

Step 5: Re-running with the Correct Event Name

Using upload_with_file_data, Claude re-ran the retention analysis. The number of target users increased to a level that matched our intuitive sense of the data, making the analysis trustworthy.

The Result

The final finding: retention rates for users who first used the recording feature vs. the file upload feature after signup were nearly identical.

Knowing that both entry points lead to similar retention was a valuable insight for our product strategy—it means we don't necessarily need to push users toward one feature over the other.

Also worth noting: because I scoped the initial instructions tightly, Claude produced the first output in about 11 minutes, and the subsequent back-and-forth corrections were equally fast.

What Worked Well → Rating: ★★★★☆ (Very Good)

The biggest value was having Claude think through the analysis alongside me, not just execute it. Other tools can generate SQL, but what Claude did here went beyond that:

Self-correcting the retention definition. Claude noticed the initial results were unrealistically high and course-corrected on its own, proposing a more meaningful metric without being prompted.

Proposing and implementing a better methodology. The shift from "any subsequent event" to "returned on a different day" was Claude's own idea.

Discovering the hidden event rename. Without being asked, Claude investigated why the user count was low, found the naming change, and re-ran the analysis with the correct data.

Why ★4 instead of ★5? Claude occasionally struggled with BigQuery's UI—accidentally opening menus or taking a few tries to click the run button. But it always recovered and completed the task, so this is a minor issue in practice.

Conclusion: Claude in Chrome as a Data Analysis Partner

What I took away from this experiment is that Claude in Chrome isn't just a tool that writes SQL for you—it's a partner that thinks through the data analysis process with you.

Going from a casual Demo Day question to actionable insight in about 30 minutes was, honestly, pretty remarkable. Even if you can't write SQL yourself, you can just describe what you want to find out in plain language and the analysis gets done. And if the results look off, Claude catches it and fixes the approach on its own.

Next time, I'm planning to have Claude help me design the product initiatives based on these analysis results.

See you in the next experiment!

Related articles

Testing Claude in Chrome: A Non-Engineer PM’s Honest, Hands-On Review

Testing Claude in Chrome 2: How I Built a Sample Meeting audio in 30 Minutes

Fathom AI Review 2026: Is It Really Free Forever? Pricing, Features & Honest Test

Return to List